Through the posters that he designed, Joan Miró demonstrated his commitment to society and to culture. He believed that artistic creation should go hand in hand with a civic sense of responsibility.

Mercè Sabartés is part of the team of the Fundació Miró’s Communications Department and the holder of a postgraduate degree in Mironian Studies from the Open University of Catalonia (UOC). In this article, she offers an insight into Miró’s facet as an activist and explains how, for the artist, his voice was inseparable from his commitment to the community.

A commitment to freedom and to upholding Catalonia’s identity

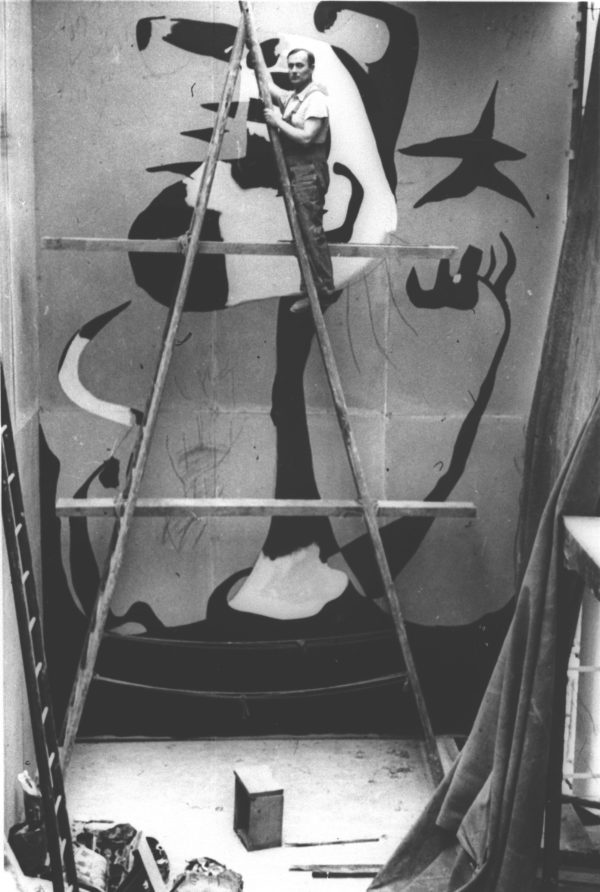

Joan Miró was an artist who was actively engaged in the events of his day. He demonstrated this through his contribution to the creation of the Spanish pavilion for the Paris International Exposition, where he made the mural Le Faucheur (1937), and also through the creation of the stamp Aidez l’Espagne to raise funds for the Republican government. However, it was undoubtedly from the 1960s that his commitment to freedom and to upholding Catalonia’s identity became more evident in statements that he made and, above all, through his altruistic wish to collaborate and be associated with causes related to culture and human rights by creating posters for them.

Joan Miró at the Spanish pavilion for the Paris International Exposition, 1937. Unknown author – Courtesy Successió Miró

From the 1940s, Miró began to take an interest in printmaking techniques that would allow him to create art accessible to a maximum number of people and to shun easel painting and monetary speculation with works of art. How? “Putting up posters in the street, as I’ve often done, or through sculptures, printmaking…,” as he confessed to Raillard.[1] Miró was interested in posters because they unite a series of characteristics that were very important for him: they are joint creations, rather akin to something anonymous, through collaboration with artisan printmakers; they are mural artworks for the whole population, found throughout our cities; and, at the same time, posters are ephemeral, because they are not conceived to last, given that sooner or later newer posters will replace them.

In parallel with the exhibition at Santa Creu Hospital in1968, there was a growth in the number of posters produced by Miró, probably because he was rediscovered by Catalan institutions in the expectation that an artist of such international repute would help draw attention to their cause. In conversations with Raillard, the artist put it this way: “They address me rather as if I were a patriarch. I’m glad they ask me for things, mainly because the official authorities have always done their best to keep me from being known in my homeland despite being very well known everywhere. That has been hard for me….”[2]

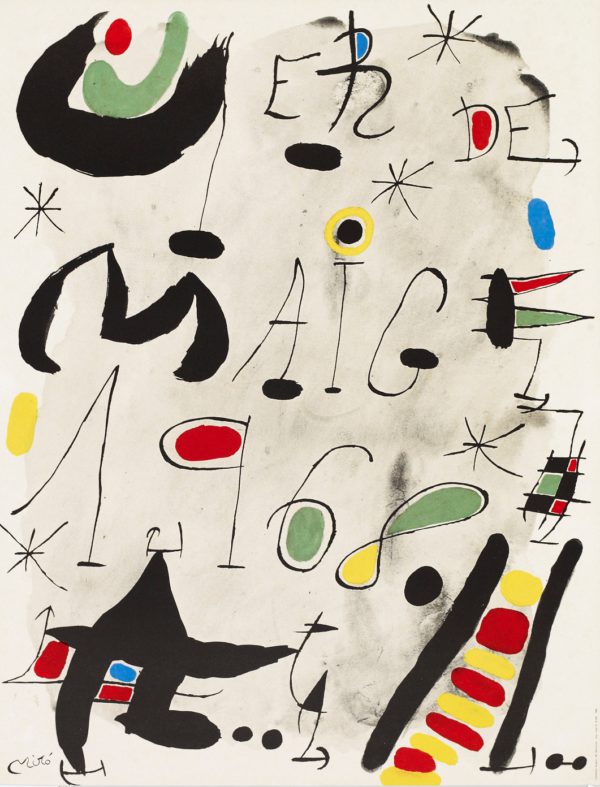

That same year, Miró made the poster for May 1st, International Workers’ Day. Pere Portabella remembers the commissioned poster: “[…] we went to see him at Hotel Colón at the request of the heads of the trade union Comisiones Obreras to ask him to do the poster for May 1st. And here is the poster, summoning people to demonstrations that were considered to be illegal at the time.”[3] In this case, Miró clearly positioned himself as being in favour of worker rights, something that had been ignored by a regime that prohibited trade unions, except for the Organización Sindical Española, which was compulsory for everyone.

1er. de maig 1968, 1968. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2019

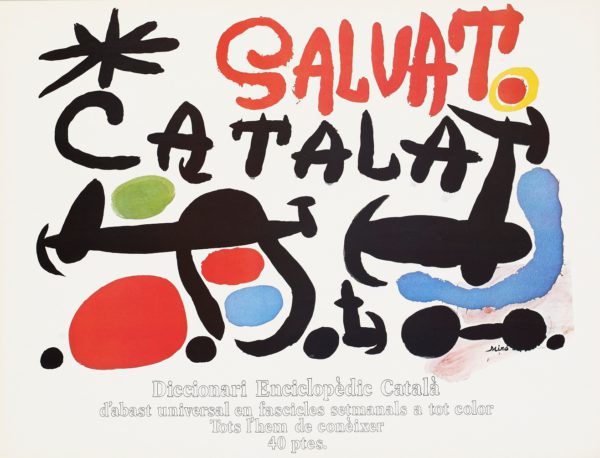

That same year, Barcelona dawned, one day, covered in posters with the slogan ‘Salvat Català’, announcing the publication of the first encyclopaedic dictionary in Catalan, published by Editorial Salvat. It was a poster with a possible double meaning, heralding the publication of the dictionary while also using the play-on-words ‘Salva’t, català’ (‘Save Yourself, Catalan’), defending the need to revive the Catalan language, following its disdain by the dictatorship and relegation to family circles.

Salvat Català, 1968. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2019

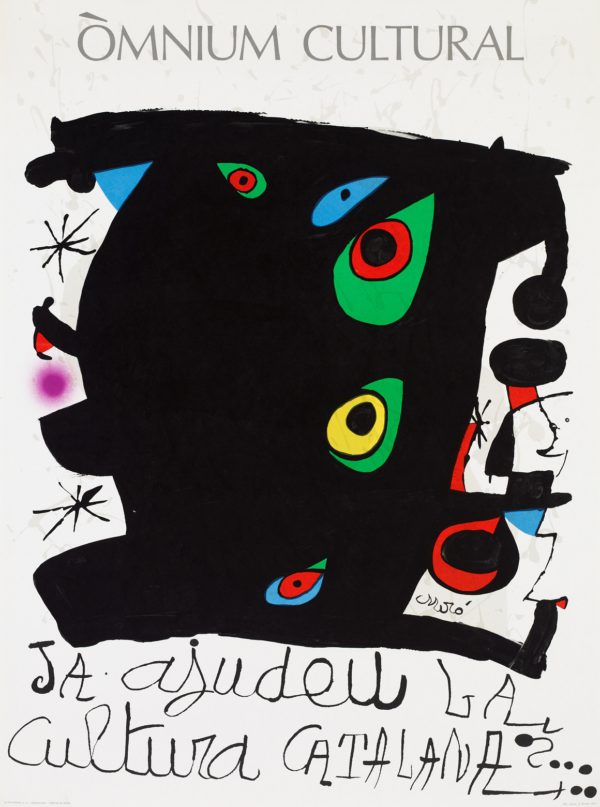

Similarly, in 1974, Miró created a poster for Òmnium Cultural, a body founded in 1961 to make up for the lack of Catalan cultural institutions. The poster asked its viewers a direct question: “Ja ajudeu la cultura catalana?” (“Do you contribute to Catalan culture?”).

Òmnium Cultural. Ja ajudeu la cultura catalana?, 1974. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2019

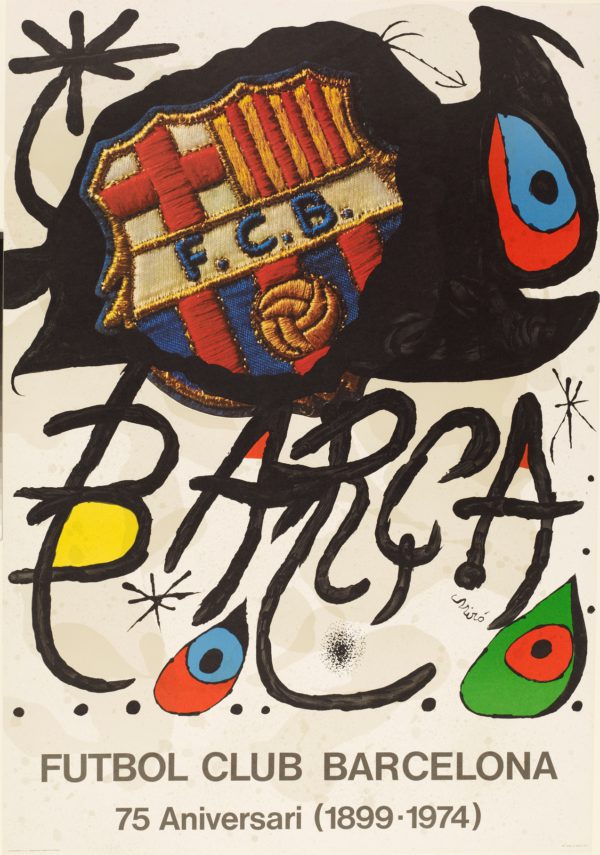

Catalan culture is more than just a language, however. A nation’s culture is made up of the whole of society, as Miró well knew, and that is why he designed the poster for the anniversary of Barcelona Football Club. In reference to the poster, Miró explained: “The last engraving is for Barça (it’s a football club–do you know it?). It’s to celebrate its 75th anniversary […]. It influences hundreds of thousands of people and it’ll be seen the world over. It’s not Barcelona: it’s the whole world.”[4]

Barça. Futbol Club Barcelona. 75 Aniversari, 1974. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2019

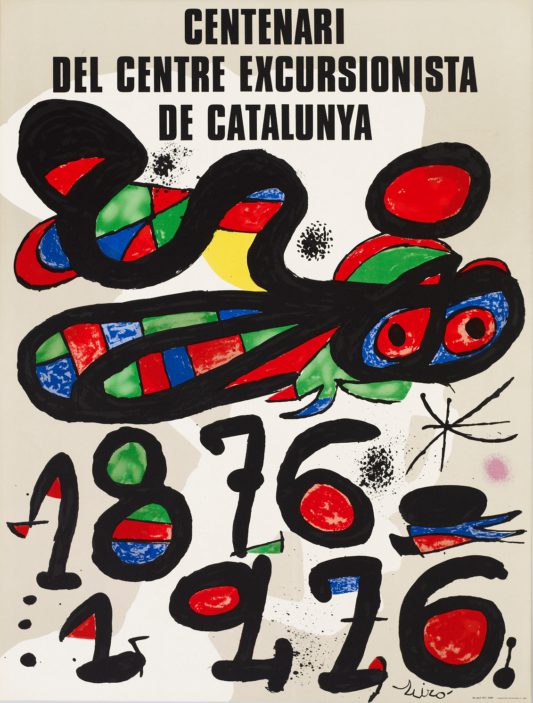

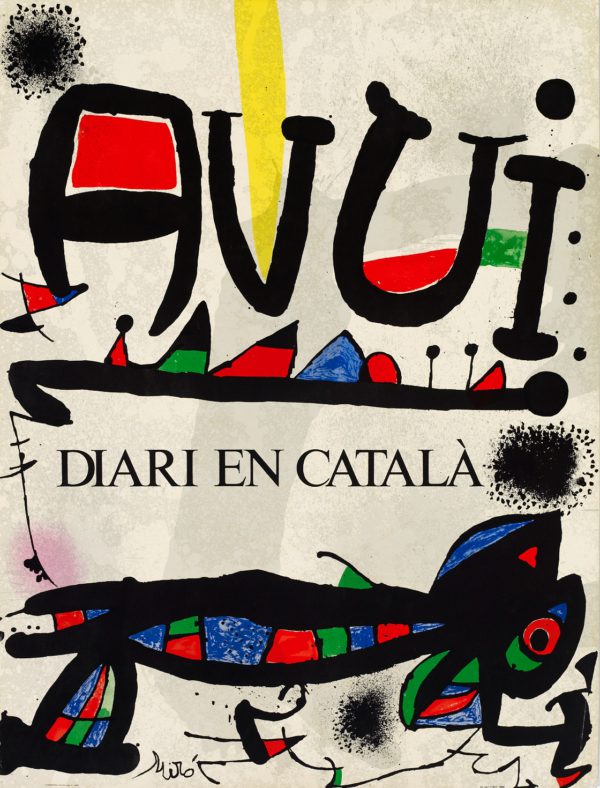

Miró’s activities as a poster designer intensified after Franco’s death: a moment of uncertainty and transition in which the whole of Catalan society called for recognition of its culture and institutions. Miró was visited by Raillard in 1975, and the starting point for their conversation was the poster that he was preparing for the launch of the newspaper Avui: “What you can see here is a project for a poster for the first newspaper in Catalan in 45 years. […] I’ve striven to support Catalan culture for forty-five years. […] And later, after the Civil War and the triumph of the Franco regime, I often felt disillusioned, but today, with this poster, something new is beginning. Just like this, a poster for Catalan hikers (image 6) […]. In spite of everything, throughout all these years, Catalonia has continued to germinate.”[5]

Avui. Diari en català, 1975. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2019

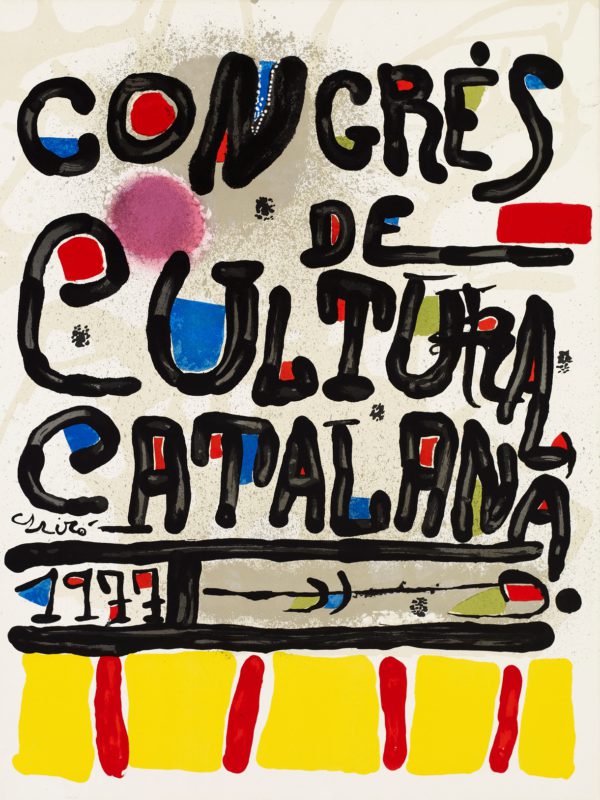

Indeed, Catalonia’s institutions strived to uphold Catalan culture. In 1977, as if in reaction to the question posed in the poster for Òmnium, a Congress on Catalan Culture was held, with a huge response by citizens. The Fundació Joan Miró presented the exhibition Què és i què ha estat la cultura catalana (What is and what has been the state of Catalan culture?), and Miró–who was always in touch with what was going on around him–created the poster for it.

Congrés de Cultura Catalana, 1977. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2019

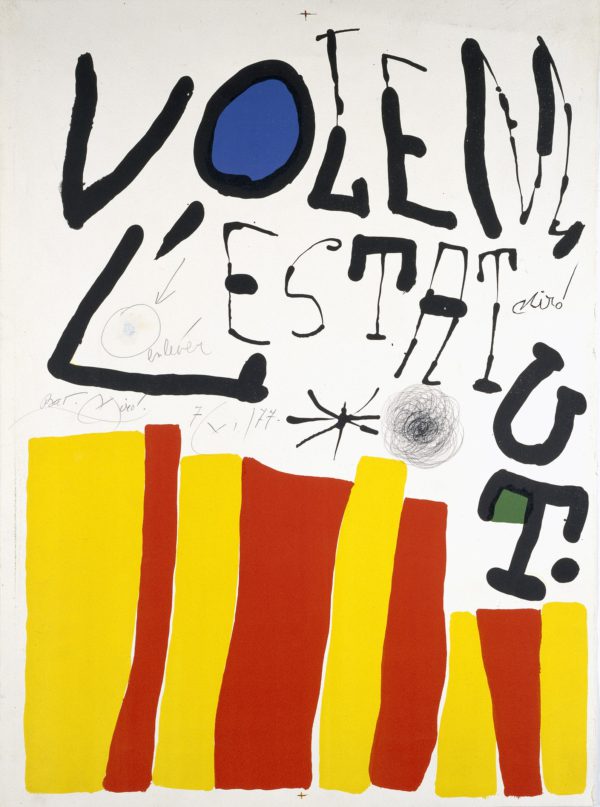

That same year, the Assemblea de Catalunya, an umbrella organization for political parties and cultural and civic organizations, launched a campaign entitled ‘Volem l’Estatut’ (‘We Want a Statute of Autonomy’), and Joan Miró was commissioned with the poster. It did not become widely known, but it had a great significance for Miró, as he remarked to Raillard: “[…] I wanted it to convey force, nothing but force […]. In Barcelona’s streets, there’s graffiti everywhere and I wanted to form part of it: using just bold strokes and the four stripes of our flag. Those posters, distributed throughout the whole city in all the streets, represent the Catalan people’s wishes, the graffiti’s wishes. […] Red, yellow, blue, green, black, very violent. Boom! The victory of vitality. There it is.”[6]

Project for the poster Volem l’Estatut, 1977. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. © Successió Miró, 2019

Through the creation of his posters, Miró demonstrated his social activism. This was very probably closely tied in with the civic responsibility that Miró deemed to be essential in art, as he clearly illustrated in his speech of acceptance of the honorary doctorate awarded by Barcelona University in 1979: “I consider an artist to be someone who uses his or her voice, amid the silence of all the rest, to say something, with the obligation that it must not be in vain; that it must be something that serves the people. That being able to raise one’s voice when most people don’t have the opportunity to express themselves […] somehow makes that voice the voice of the community. When artists raise their voices in a nation like ours that has been cruelly marginalized by adverse historical events, they must make themselves heard throughout the world in order to affirm–contrary to all ignorance, misunderstandings and bad faith–that Catalonia exists; that it is original, and that it is alive.”[7]

[1] Raillard, Georges. Joan Miró. El color dels meus somnis. Converses amb Georges Raillard. Palma: Lleonard Muntaner Editor, 2009, p. 26.

[2] Raillard, Georges. Conversaciones con Miró. Barcelona: Gedisa, 1993, p. 233.

[3] Portabella, Pere. «Miró l’altre». A: Malet, Rosa Maria. Joan Miró 1956-1983. Sentiment, emoció, gest. Barcelona: Fundació Joan Miró, 2006, p. 44.

[4] Miró, Joan. Miró parle. Paris: Maeght éditeur, 2003, p. 31.

[5] Raillard, Georges. Joan Miró. El color dels meus somnis. Converses amb Georges Raillard. Palma: Lleonard Muntaner Editor, 2009, p. 19.

[6] Raillard, Georges. Conversaciones con Miró. Barcelona: Gedisa, 1993, p. 232-233.

[7] Speech by Joan Miró on his receipt of an honorary doctorate by Barcelona University, October 2nd 1979. A: Malet, Rosa Maria. Joan Miró. Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1992, p.7. (Pere Vergés collection; 47).