Throughout lockdown and the period of the “new normal,” we have been able to explore new settings for art and for our ways of relating to each other. We have upended the boundaries between the public and the private, between the analogue and the virtual, between exhibitions and political statements. Reflecting on the crisis generated by the pandemic, writer, social educator and activist Amadeu Carbó explores the possibilities of new, increasingly democratized and democratizing spaces for culture and art.

From the New Normal to the New Reality

We have had more than nine months to digest and adapt, to whatever extent possible, to living with the pandemic generated by COVID-19. Less than a year ago, none of us who live on the bright side of the earth, those privileged few in percentage terms, could begin to imagine that a virus would be capable of placing us in a precarious state in which we stagger ahead into uncertainty, both individually and collectively.

I must say that, despite the legitimate, reasoned and justified demands of the world of culture, the situation of neglect we are experiencing is not much different from that in other sectors which are not fortunate enough to have the necessary tools or resources for raising their voices and making themselves heard; they are invisible. By this I mean that this neglect is more cross-cutting than sectorial, and the crisis is more systemic than strictly health-related. The main issue at hand may be one of class – more specifically of the working class, a concept we have forgotten but which continues to exist.

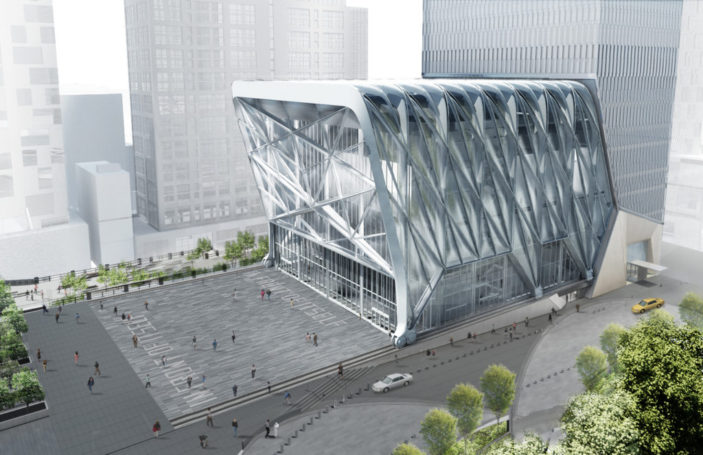

Like a giant with feet of clay, everything has fallen apart in a flash. And this leads me to believe that not everything may have been built on solid foundations, nor as well shored up as we assumed. For the major cultural institutions that had been plodding and creaking along since 2008, the blow has been dreadful. We must not lose sight of the fact that many of these institutions were established in the image of grand mausoleums displaying the personal ostentation of their board members and satellites. In fact, they are not much different from the Boards of Directors of banks and multinational corporations, following in their footsteps, using their models and even sharing their names.

Ultimately, as often happens, the victims – those who end up bearing the brunt of it all – are and will continue to be the cultural workers, and I will go back to the class argument I referred to above: the specificity of “cultural workers” does not make them any different from other workers, who are the weakest link in the entire system, a system which in our neoliberal case is no minor detail.

But now is the time to look ahead and turn the misfortune into a blessing. Faced with an entirely collapsed cultural system, we could look at it simply as a collapsed system, and find new strategies and resources to continue generating culture. In this case, it may be a good idea to apply a radical perspective, like Miró in his quest to assassinate painting, without making compromises, be they technical, methodological or institutional. We are facing a new era; there is even talk about a new social contract, in which we will have to pay attention and listen to what it is trying to tell us and what we, in turn, can offer it.

Obviously, everything is not going to be alright. We can see that every day; the magnitude of the pandemic disaster keeps on growing and not everyone will make it through. Those who show a true ability to experiment, to adapt, to develop new discourses and make new proposals that are attuned to the “new reality” will be the ones to get ahead – those who are resilient.

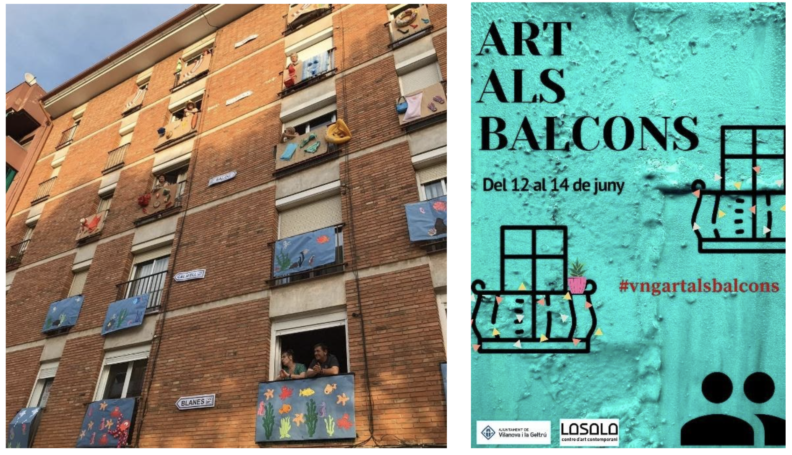

This “new reality” is what I would like to stop to consider. Throughout lockdown and the “new normal” period, we have been able to play around and experiment in new realms that already existed, but which we had not yet explored in depth; it was still uncharted territory for most of us mere mortals. Spaces that were conventional until now have had their boundaries blurred, leading precisely to new spaces that no longer involve a physical location – a room, a stage, a workshop.

Likewise, the notion of community has also experienced a huge blow. Communities understood as groups of humans interacting in shared spaces – where the academic definition considers a shared space to be a physical space – have also been conceptually dismantled, leading to new construction in which physical space is no longer the centre of activity, relationships, and so forth.

Activity going virtual and the use of social media first served as a poultice that acted as a cultural pain-killer of sorts, particularly during the lockdown’s hardest moments. Providing open access to contents, even as an extension of the “old reality,” was a first step that hinted to the fact that we were on the verge of experiencing profound changes in the way we consume, display, and also generate culture.

In the midst of the lockdown period, in an op-ed article, I wrote that “if we are capable of moving young children’s learning online, shop for our essential needs on websites, work with an entire team of connected colleagues, meet people and have sex on an app, attend religious services on YouTube, receive medical assistance on our smartphones, and share meals and drinks with friends and family on Zoom, what can stop us from celebrating our festivities online?” Now I would add, what can stop us from carrying out cultural activities? And I would place the accent on creativity. Personally, I find the prospect daunting, but also believe it could be an extraordinary challenge. However, we must engage in a reflection and take a critical view to acknowledge that the networks and online environments we are using are not appropriate for cultural activity. First of all, because they are neither ethical nor transparent, and the companies and multinational corporations behind them do not line up with the values that the arts supposedly uphold; therefore, we will have to avoid them or be very selective.

Accordingly, it is up to us to demand from our public administrations that they support public tools and social media that are ethical and respectful with their users’ privacy, and become a basic public service. Considering social media as a public service will be a huge step towards democratizing many processes, including those involving culture.

We are probably facing a situation that shares many common denominators with that of Western culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A crisis situation that took us a step further, bringing about an urge to break the conventions and academic boundaries that were holding back an unprecedented creative potential, the outburst of which resulted in the rise of avant-garde movements, new forms and new messages. A new way of seeing and looking at the world from a creative perspective. We will have to wait and see whether the cultural institutions that have risen from the “old reality” will be receptive and proactive, both culturally and creatively, towards what the “new reality” supposedly has to offer us.