Museums collect and exhibit the most familiar side of artists, their works of art. In their effort to make them known, however, certain anecdotes are often lost, many of which will only come to be revealed by chance or through the tenacity of someone with a curious, analytical approach. Pedro Azara, architect and Professor of Aesthetics at the Barcelona School of Architecture, has uncovered a facet of Miró’s personality, of his way of approaching things and of relating with his friends, revealed in the determined coherence of a gesture.

Letters that matter

In late 2016 and early 2017, thanks to a permit obtained from Christophe Tzara, son of the great poet Tristan Tzara, the architect Marc Marin and I obtained access for a few weeks to the modest Jacques Doucet Library, in the Latin Quarter of Paris (Christophe would die a year later). In doing research into the correspondence of Tzara, I had the opportunity to read his exchanges with Joan Miró. While Miró was never a writer like Picasso or Dalí, the texts revealed other aspects of the artist. In the middle of a batch of letters and postcards, I was able to read Miró’s correspondence with various publishers and with a printing studio. The letters Miró sent to other artists (painters, poets) and his dealers, publishers and workshops, often dealt with art-related subject matter: engraving techniques, works pending, exhibitions, and so on. Only on rare occasions do they speak of personal details beyond his travels and messages of best regards as a friend, always polite and sincere. Brief messages it would be hard to put a biography together with.

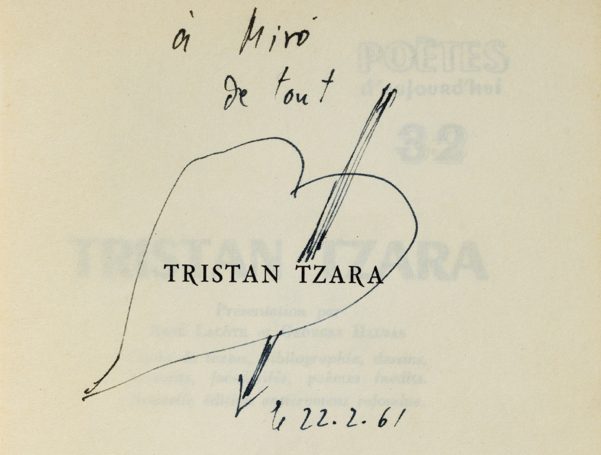

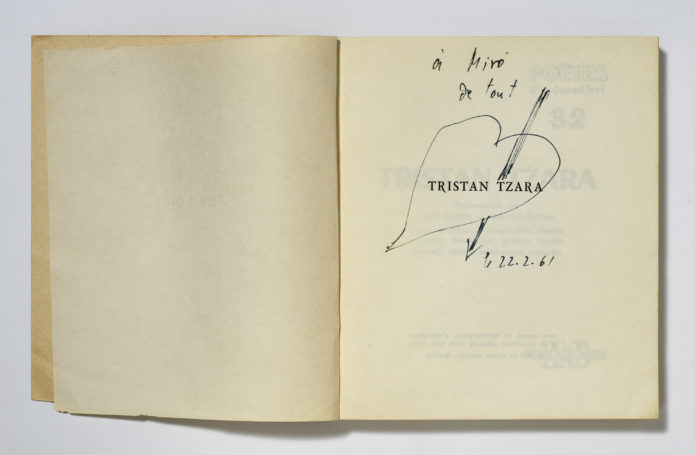

René Lacôte: Tristan Tzara, 1952. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. On loan from Successió Miró.

Despite this, a very short letter sent to Tristan Tzara, mixed in with many others amongst piles of paper, revealed other concerns. Using an altogether different tone, his letter did not ask about the conditions of certain works or the quality of the materials. He was not querying about the density, texture or weight of paper; neither was he interested in the inks used nor the pressure on the plates nor printing techniques, all of which were details that Miró spent a great deal of effort on, dedicating detailed attention to them. In this case his concerns were aroused by the destiny of a friend.

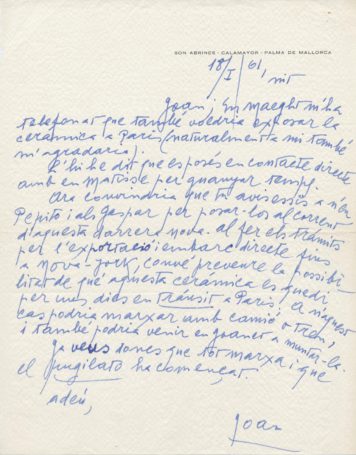

Letter from Joan Miró to Joan Prats, January 18, 1961. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. Donation of Manuel de Muga

Miró lived at number 98 Boulevard Auguste-Blanqui, in the 13th district of Paris. The vaguely art nouveau Haussmannian block with its white façade was seven stories high; built in 1914, it is still there in good condition. In the same building lived Paul Nelson, a modernist architect resident in Paris who was a collector of Miró’s work and a person he had collaborated with on a project which was ultimately never made, the Maison Suspendue.

On 15 February 1939, Miró (most likely in exile from Barcelona, where he had lived during the Civil War before setting up in southern France) wrote to the poet Tristan Tzara. He asked him to intercede on behalf of the surrealist painter Antonio Rodríguez Luna, an artist who had shown in the Pavilion of the Spanish Republic at the Paris International Exhibition of 1937. At that time his friend was being held in a concentration camp in Argelès, in France, and his health was failing: “Sa santé est si précaire et de rester là sa vie serait en danger” [His health is so poor that if he stays there his life will be in danger], wrote Miró in perfect French. He then requested if Tristan Tzara could intercede as well for his friend and patron Joan Prats, to have him freed as well.

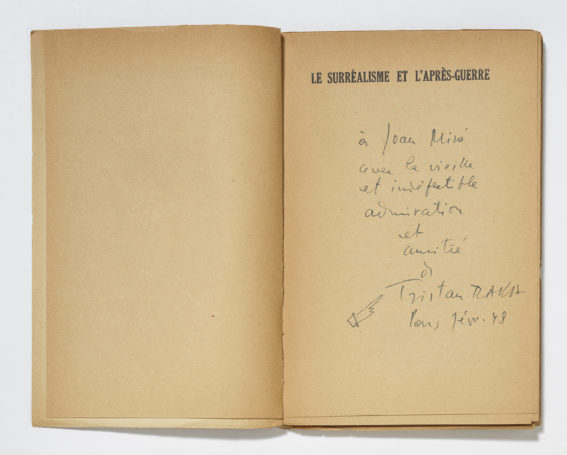

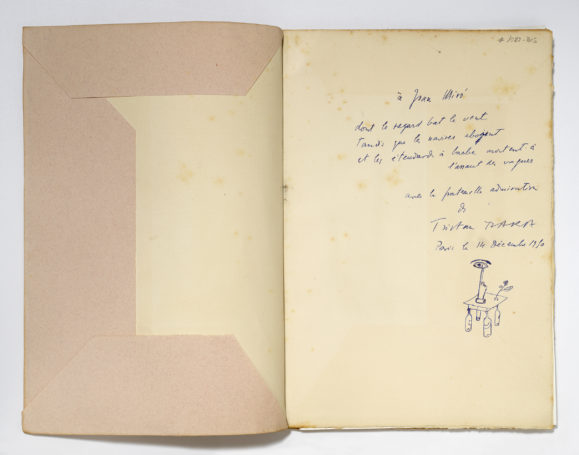

Tristan Tzara: Le surréalisme et l’après-guerre, 1947. On loan from Successió Miró.

One month later, on 21 March 1939, Miró wrote to Tzara again to thank him for his efforts, and explain to him that Rodríguez Luna had already left the camp and was living in a flat in Paris belong to Monsieur de Jouvenel (most likely Renaud de Jouvenel, a communist writer and member of a renowned family of French politicians): “C’est pour lui comme un rêve après un cauchemar” [For him it is like a dream after a nightmare].

The biography of Rodríguez Luna includes the intervention of Miró, but not that of Tzara. For his part, it would seem that Prats had indeed been held prisoner, but not in a French concentration camp—he was in Spain. After this episode, the letters exchanged between Miró and Tzara returned to commenting on art-related subjects and artistic techniques.

Tristan Tzara: Indicateur des chemins de cœur, 1928. On loan from Successió Miró

A single letter has corrected a version of history, but this is not its sole worth. The letter reveals the face—perhaps the true visage—of a friend helping other friends in a moment when writing to the wrong person at the wrong time could lead to someone’s death. The only evidence of Miró’s gesture to assist Rodríguez Luna and Joan Prats is from this written correspondence with Tristan Tzara. It is a letter that does not reveal an artist’s usual concerns, as would be habitual for Miró, but another aspect of his personality that could point to untold, subtle features in his artistic work.

1 Jacques Doucet Library, Paris, signature MsMs 43972.

2 Jacques Doucet Library, Paris, signature MsMs 44005.