Lina Bo Bardi Drawing is an exhibition about the architect’s deep sense of connection with drawing. For her, drawing was more than a designer’s tool; it was a primary expressive means driven by a strong sense of curiosity and doubt. In the following article, the architect and exhibition curator Olga Subirós shares some of her memories to offer us a closer look at Lina Bo Bardi’s work.

Rock, Paper, Circus

In 2003 I spent two weeks in São Paulo with my son, who was a little over two at the time. We visited three works by Lina Bo Bardi: the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP), the Glass House, and the SESC Pompeia cultural centre. It was a gift to be able to visit them with him.

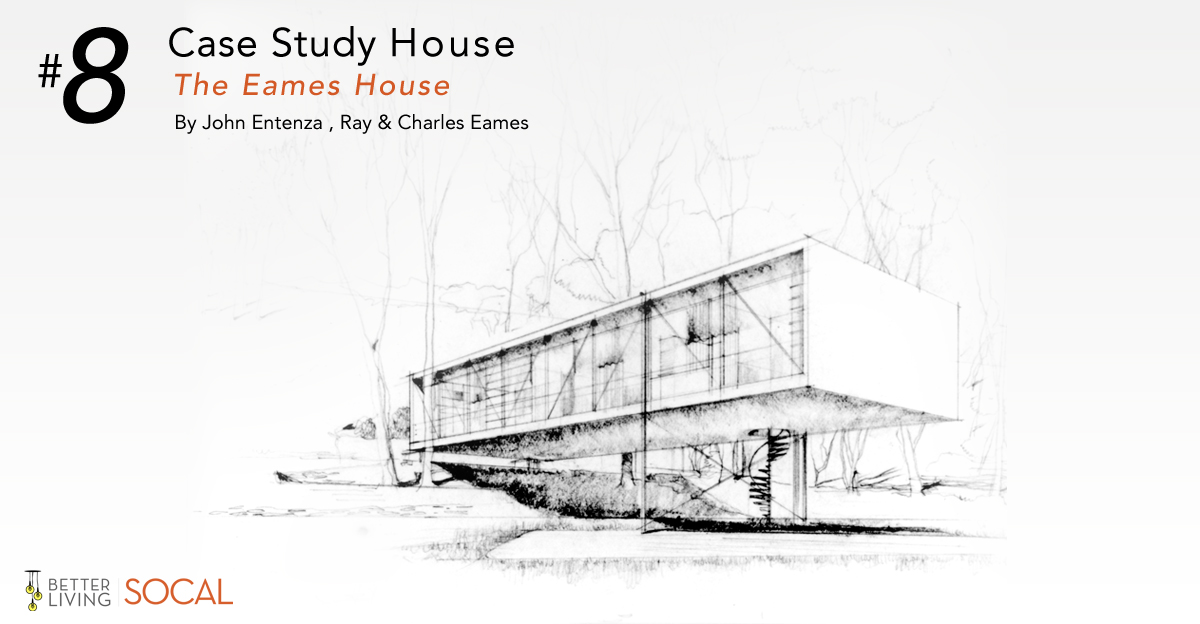

I remember carrying him in my arms around the Glass House (1950-51), feeling the emotion of climbing the stairs in a house perched among the treetops, and finding an open space full of objects with the forest in the background. Our eyes skipped from one piece to the next in a space that was ideal for discovery. At the same time, my thoughts continuously wandered back to the Case Study Houses in Los Angeles, especially the first version of Case Study #8, by Ray and Charles Eames (1945). Both houses express the sense that, after World War II, a new world was possible. A transparent, democratic, flexible, fluid world where architecture would be prefabricated, inexpensive, efficient and beautiful.

Casa de Vidro, Lina Bo Bardi (1950-51). © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Casa de Vidro, Lina Bo Bardi (1950-51). © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Case Study House #8, Ray and Charles Eames (1945). Drawing published in Arts & Architecture magazine, December 1945

Walking through the garden we came across a wood cabin hidden away among the plants. It was painted green and had been Lina’s studio; at that moment, it was the main office of the Instituto Lina Bo Bardi. It had the air of a cabin for thinking, for focusing on work, on design, as an intimate act; a place for playing as you draw, for thinking with your hands.

The visit to the MASP left us wide-eyed and open-mouthed. I think we both experienced the same feeling of both weight and weightlessness, the potential of that vast space opening up to the city under the shelter of its massive structure.

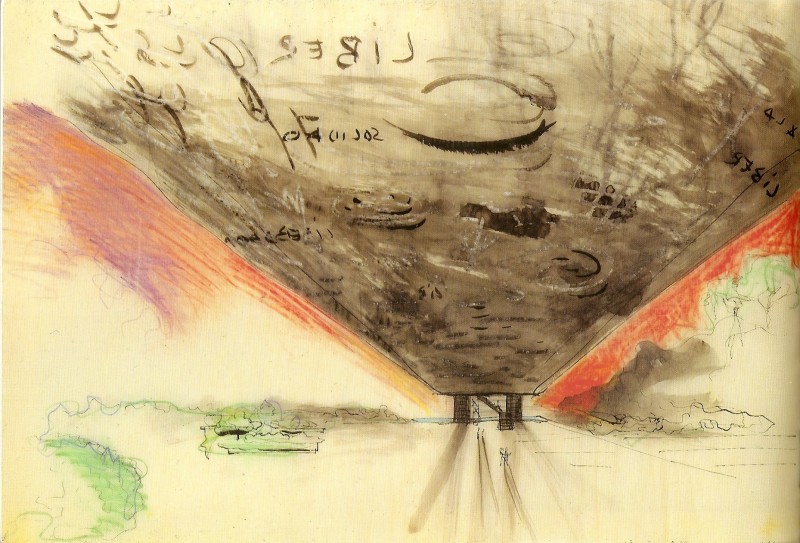

Perspectiva do Belvedere. MASP, Lina Bo Bardi (1957-68). © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Perspectiva do Belvedere. MASP, Lina Bo Bardi (1957-68). © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Perspectiva do Belvedere indicando instalação do circo Piolim. MASP, Lina Bo Bardi (1957-68). © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Perspectiva do Belvedere indicando instalação do circo Piolim. MASP, Lina Bo Bardi (1957-68). © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

The sketches Perspectiva do Belvedere and Perspectiva do Belvedere indicando instalação do circo Piolim transport me back to that moment: one of them shows us the void, and the other, the possibility of hosting any kind of event, all the potential of a public space. Zooming into the drawing, it looks as though Lina were asking us, “Rock, paper, circus?”, but we don’t really have to choose. Everything is offered to us with the same value: nature and the arts. It isn’t arbitrary, I view it as a manifesto. Lina draws a public, democratic space, open to celebration and participation.

“When the American musician and poet John Cage travelled to São Paulo, when his car was going down the Avenida Paulista, he asked the driver to stop next to the MASP. Cage stepped out and walked from one side of the belvedere to the other, raised his arms, and exclaimed: ‘It’s the architecture of freedom!’ I was used to praise for having made the largest free span concrete structure in the world with a permanent load and a flat roof, but the great artist’s statement conveyed what I considered essential in the MASP project: the museum was NOTHING, it was the elimination of obstacles, the ability to be free in relation to things”.[1]

Inside the MASP, Lina Bo Bardi’s proposal for displaying the art collection was not applied, but it was etched in my memory: the exhibition hall inhabited by the pieces with which Lina seems to invite us to play heads or tails. All the works welcome us with their heads, like a crowd waiting to engage in a dialogue with us, without mediation. Heads are the pure experience of the piece, and tails are where Lina leaves a space for interpretation: title, artist, date, technique. It is a game in which she invites us to actively engage. Freeing a work of art from the wall is an exercise that Lina Bo Bardi had witnessed in other designers such as Franco Albini. For Lina Bo Bardi, the point is not to achieve an interesting design effect. The aim is more radical –that of understanding the reception of art as the experience of stepping forth to encounter the other, the unknown, opening up to curiosity and amazement.

MASP painting collection. © Paulo Gasparini/Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Franco Albini, Pinacoteca di Brera, Mostra di Scipione e del Bianco e Nero, Milan (1941). Photo: Fondazione Franco Albini collection

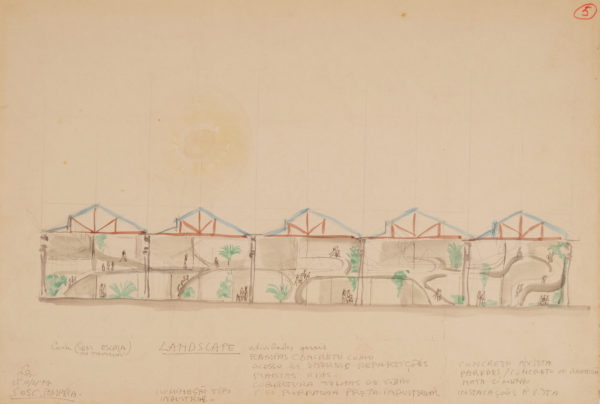

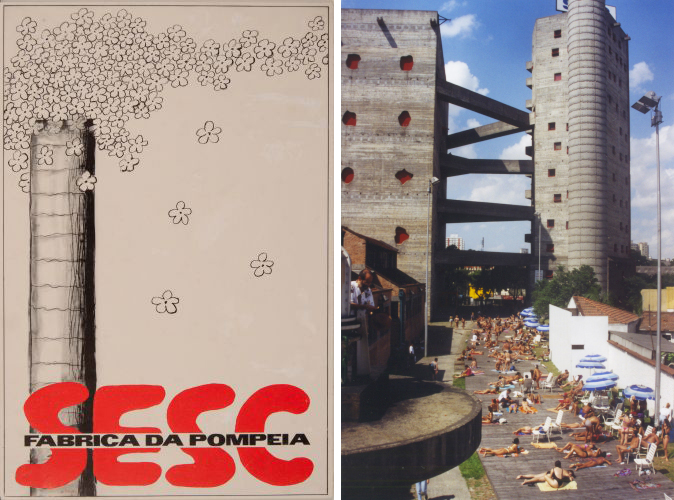

We visited the SESC Pompeia cultural centre (1977-86) three days in a row. I cannot imagine a better way of experiencing the SESC than with my son. We explored that city of sorts full of tucked-away corners and buzzing with activity. We started off in the library, where we leafed through storybooks in the company of chess players; we watched sports activities and took a dip in the pool; we saw people going to the health care centre and sat to watch a little comedy performance for raising awareness about sexually transmitted disease prevention. Strolling through an interior landscape full of plants, we crossed a brook that led us to an Antoni Abad exhibition; visiting the arts and crafts studios we got our faces and hands dirty; we shared a table in the cafeteria and then took a nap. We saw children and everyone else at play, and we felt we were part of them; as we played, we had a sense of belonging to the place. By doing almost nothing, Lina Bo Bardi achieves everything: a factory that had housed a production and operation centre becomes a place that opens up to living, exchanging, caring, creating, learning –in other words, to culture.

“Nobody changed a thing. We found an architecturally powerful, original factory with a beautiful structure: nobody touched it. […] All we did was add a few things: a bit of water, a chimney. The original idea for repurposing the complex was informed by architettura povera, not in the sense of its being impoverished, but in the artisanal sense of achieving the highest degree of Communication and Dignity with minimal, humble means.” (Lina Bo Bardi por escrito, p. 192)

Lina Bo Bardi invites us to play. To play in the most political and social meaning of the word, by creating public spaces for celebrating coexistence and mutual care in the broadest sense. To play at merging with our surroundings, without hierarchies, in a place where presentation and representation, tradition and modernity, the living and the inert, the human and the nonhuman coexist in freedom.

Activity hall at SESC Pompeia, Lina Bo Bardi (1977) © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Rio São Francisco do SESC Pompeia, São Paulo, 1977. Fotografia: Antônio Saggese

Logo for SESC Pompeia, Lina Bo Bardi (1977-86) © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Logo for SESC Pompeia, Lina Bo Bardi (1977-86) © Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi

Sunny Sunday at SESC Pompeia. Photo: Marcelo Ferraz

[1] Lina Bo Bardi, Una clase de arquitectura, São Paulo School of Architecture and Urban Planning, 1989. Source: “La gran vaca mecánica”, by Mara Sánchez Llorens, published in the magazine Circo 2010-161, Madrid.