Mont-roig is a small village in rural Tarragona that played a decisive role in the course of Joan Miró’s life and work. In this text, the Fundació’s curator Elena Escolar offers us a slow-motion description of Mont-roig, the Church and the Village, painted in 1919 and presented in the special Catalan art section of the thirteenth Salon d’Automne in Paris, in 1920, almost one hundred years ago. To grasp Joan Miró’s intangible universe, it is essential to have a sense and an understanding of the landscape and the land itself in Mont-roig.

Mont-roig, Understanding the Landscape

Barcelona, Paris and Mont-roig are key landscapes for understanding Joan Miró’s work. In Barcelona, where the artist was born, he met the owner of Galeries Dalmau, a major promoter of European avant-garde art at whose venue Miró had his first solo show in the winter of 1918. Shortly thereafter, in 1920, Miró made his way to Paris, where he settled permanently in 1921. Both Barcelona and Paris opened up his intellectual and artistic horizons to the avant-garde: he met artists, poets, dealers, and frequented cafés, museums, bookstores, artist’s studios, and collectors. However, it was in Mont-roig, a small village in rural Tarragona, during the summers he spent at the Mas Miró farmhouse, that many of the decisive moments in his development as an artist occurred. Mont-roig became a crucial landmark in the path of his art and life, the place to which he always returned.

Olive, carob, pine, almond and fig trees make up the landscape along with vineyards; open fields sowed with grain abound, as do vegetable gardens watered by irrigation ditches flowing from farmhouse reservoirs. The village spreads from the Colldejou and Llaberia mountains to the sea. Miró often went walking or jogging down the seashore.

Mont-roig is where he became immersed in the cycles of nature. He watched the insects, the animals in the wild, the stars, the clouds, the effects of the sun and the moon, the gradations of light on the landscape, the impact of the rain on the red soil. He lived among the peasants, was imbued by their wisdom, shared meals with them, listened to their stories, watched them work the land, the tools they used, the objects surrounding them, and the effect of the cycles of nature on their everyday lives. The area surrounding Mont-roig and its protagonists, seen in detail, stimulated the artist to integrate the landscape, which he not only captured formally, but which actually became a creative force and awakened a sense of belonging in Miró: “It’s the land, the land. It’s bigger than me. The fantastic mountains play a very important role in my life, and so does the sky. […] it’s the collision of these forms in my mind, more than the vision itself. In Mont-roig, it’s the force that nourishes me, the force.”[1]

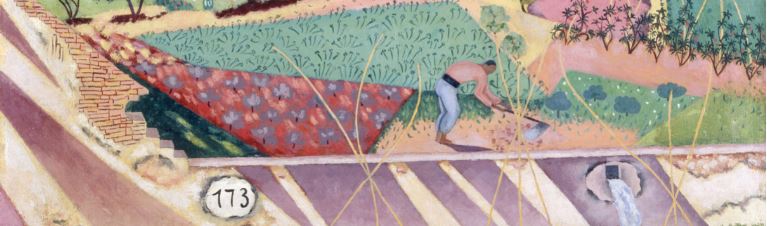

Detail of “Village and church of Mont-roig”, Joan Miró, 1919. © Successió Miró

In the summer of 1918, he painted several landscapes from nature near the farmhouse: Vegetable Garden with Donkey, The Rut, House with Palm Tree and Tileworks at Mont-roig. These pieces show a clear desire to represent the elements in the landscape in minute detail: “Joy at learning to understand a tiny blade of grass in a landscape. Why belittle it? A blade of grass is as enchanting as a tree or a mountain. Apart from the primitives and the Japanese, almost everyone overlooks this which is so divine. Everyone looks for ands paints only the huge masses of trees, of mountains, without hearing the music of blades of grass and little flowers and without paying attention to the tiny pebbles of a ravine –enchanting.”[2] Here Miró reveals some of his points of reference: Far Eastern painting and that of the “primitives” – referring to the painters of Gothic Catalan realism.[3]

During that summer and into the autumn of 1919, he painted another “detailist” landscape, Mont-roig, the Church and the Village, which closed this series of paintings. Unlike the others, the format for this piece is vertical, and this orientation is what allows us to perceive the landscape as a sequence of layers. In the foreground we see ploughed fields, cultivated plots and stakes with tomato vines. From there we move on to the middle ground in the painting, where we see water flowing from the irrigation spout in a space that is delimited by a painstakingly rendered brick wall that frames a terraced field with a variety of crops and a human figure digging furrows with a hoe. This carefully organized space contrasts with that of the upper section, where overflowing trees and vegetation pile up and spill over, leading us to the upper section of the canvas. Here, we find a detailed rendition of the old church and the rows of other buildings in the village.

The artist conveys his success in overcoming the obstacles he encountered in his creative process: “I have studied a lot this summer. My two paintings have been changed a thousand times. I am just beginning to see something. I am pleased with the one of the village; after much studying I have gradually seen — intense joy — the marvels of light, the unfocused images about which Cézanne, our great precursor, spoke. Imagine the tremendous joy of working a long long time and discovering new problems! I have not undervalued any aspect of reality: I’m convinced that everything is contained within. There is nothing superfluous (no shadows, no reflections, no twilight) — the thing is to paint it.”[4]

“Village and church of Mont-roig”, Joan Miró, 1919.Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. On loan from a private collection.

Joaquim Gomis: view of Mont-roig del Camp, 1946-1950 © Joaquim Gomis. Hereus de Joaquim Gomis. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona.

In fact, everything in the painting appears in reality, and therefore, if today, one hundred years later, we look at the same place in Mont-roig, most of the formal elements in the painting are still there. Yet in Mont-roig, the Church and the Village, Joan Miró goes beyond representing the landscape. He engages us in his experience and understanding of the landscape, and presents us with Mont-roig — the visible and the tangible along with the invisible and the intangible.

Notes:

[1] Joan Miró, El color dels meus somnis. Converses amb Georges Raillard, Palma de Mallorca: Lleonard Muntaner, 2009, p. 33.

[2] Letter from Joan Miró to Josep Francesc Ràfols. Mont-roig, 11 August 1918. ROWELL, Margit. Joan Miró: Selected Writings and Interviews. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1986, p 57.

[3] M.J. Balsach: Cosmogonies d’un món originari, Barcelona: Galàxia Gutenberg / Cercle de Lectors, 2007, p. 23.

[4] Letter to Josep Francesc Ràfols. Mont-roig, 21 August 1919. ROWELL, Margit. Joan Miró: Selected Writings and Interviews. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1986, p. 63.