- Dates

- —

- Curated by

- Evelyn Weiss

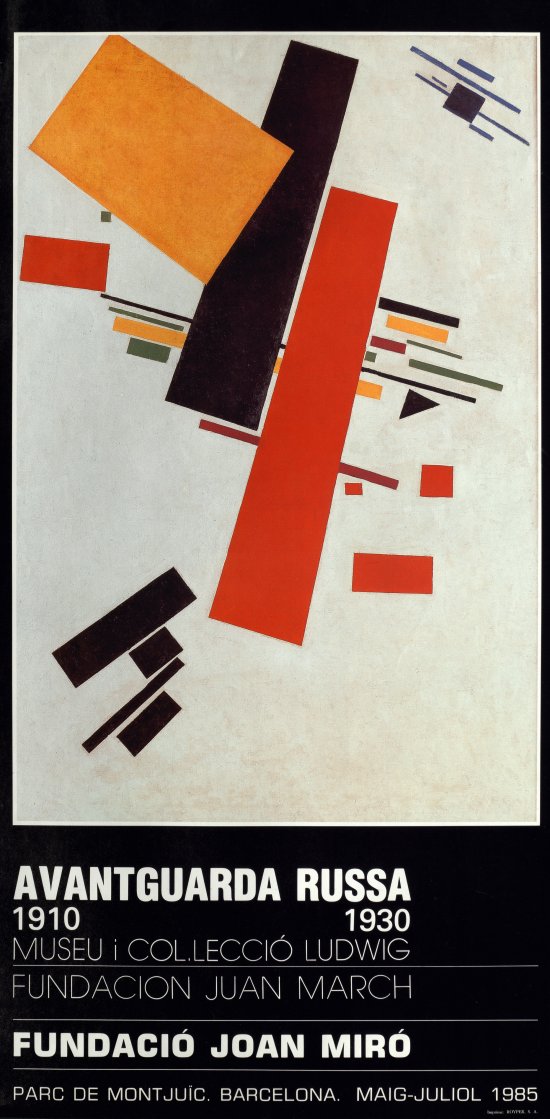

Russian Avant-garde, 1910-1930. Ludwig Museum and Collection

The history of art between 1910 and 1930 is the history of the great adventure of 20th century art. Throughout these two decades, all the innovations and surprises that we have experienced in the field of art over the past fifty years seem to have been thought out and preconceived. Throughout these two periods, there seems to have been a concentration of spiritual and intellectual forces that would in turn determine an unusual integration of the visual arts with politics, literature, music and design. It is only now that we are beginning to become aware of all the revolutionary advances we have witnessed since the 1960s, which refer back to the ideas and concepts of the Russian avant-garde.

Russian artists also dared to go to extremes, to go to the limits that would later, in the 1950s and 1960s, be formulated again by American painters of the sublime, from Barnett Newman to Ad Reinhardt.

It is true that the examples suggested here are the most striking messages of this surprising artistic panorama. But they are only the emerging part of an entire evolutionary process that began in Russia before the Revolution and that introduced a different major voice into the heart of the European avant-garde. Direct contact with the Parisian art scene and encounters with Fauvism, Cubism and Italian Futurism were obvious stimuli, but they were also touchstones that would serve to examine one’s own situation and trace the course of art’s ultimate roots.

Important works by N. Goncharova, M. Larionov, A. Lentulov, among others, mark the contribution of Neo-Primitivism to Russian art, as they were presented at the exhibition Donkey’s Tail in 1910-1912. The encounter with the theories of Italian Futurism, as formulated by Marinetti as early as 1913, led to the Rayonist Manifesto, which Larionov published in the same year on the occasion of the Target exhibition. These artists were well aware of Cubism; they discussed it and studied its works. A unique, unmistakable and vital style emerged from all these trends: Cubo-Futurism. Exceptional works in the Ludwig Collection document this stage of overall development: for example, famous paintings by L. Popova and A. Ekster, works of excellent quality. It is especially worth noting here the major role played by L. Popova and A. Ekster in the field of Russian art, both before and after the Revolution.

On the other hand, it is surprising how prominent women have been in the development of Russian art since the beginning of the century. The long list of names and works is almost unbelievable: Ksenia Ender, Vera Yermolaeva, Aleksandra Ekster, Natalia Goncharova, Yelena Guro, Nina Kogan, Valentina Kulagina, Natalia Yureva, Lyubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova and Nadezhda Udaltsova. And these are merely the main names. Some of them were wives or partners of other artists, but their work and influence were never overshadowed by them. It is fair to say that these women developed their creativity freely and held important positions and official ranks as teachers in art schools and academies, and even as directors of newly founded educational institutions. Art for them was not a salon activity and leisure pursuit, but a true profession and vocation.

As can be seen from these few remarks, this development in Russia did not proceed in a straight line. There were always overlaps, temporal differences, repetitions and various stylistic currents that remained side by side. So it happened that Malevich’s formulation of Suprematism, so important for all of 20th-century art and so superior to other tendencies, was not a final point either, but one of many existing artistic possibilities. An artist reached a limit here. Even more so, it also opened the way to many of the possibilities of abstract art that were to be formulated later. Malevich’s Suprematism not only inaugurated the philosophical dimension of art, but also made possible the further post-revolutionary development of a constructive and utilitarian art that would emerge in an exemplary manner with the Constructivism of A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova.

After the Revolution, Soviet art set standards in typography, photography, design or poster layout that are still valid today. There was a sense of joy that many experimental ideas of a revolutionary nature had finally been put to use in art. One was no longer satisfied with sculptures, beautiful objects or paintings; on the contrary, one was happy to create fabrics, furniture, porcelain and everyday objects, to design buildings in the spirit of the Revolution, or to plan proclamations, manifestos, posters and other written material. Artists were involved in architecture, machine design and mass production. Art seemed to encompass all areas of social life, from political marches and parades to theatrical performances and cinema. To summarise and extract from the essential, it can be said that in the two decades that this period covers, before and after the Russian Revolution, a total work of art was created, both artistic and social, with its own unique character. The Ludwig Collection represents a major contribution to the attempt to examine the traces of and to reconstruct, if only in part, this total work of art.

Evelyn Weiss