- Dates

- —

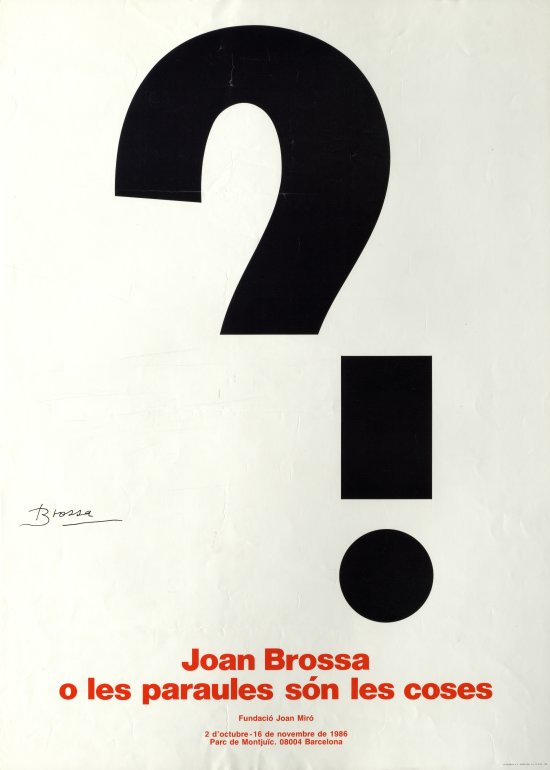

Joan Brossa or Words Are Things

Thinking with the eyes

Joan Brossa is a poet who often treats words and sentences as if they were objects. It is therefore logical that he also treats objects as if they were words or sentences.

This reciprocity explains his stated interest in show, theatre, circus, mime, music hall, sleight of hand, puppetry, etc., where both verbal images and wordless literature abound.

The show he likes is traditional, established, the one with popularly accepted formulas that, like rituals, possess a magical potential.

The clown is able to move us through gestures, costumes, attitudes that are fully codified, like the puppet with its established typologies.

Brossa has often offered us a theatre with stagings of fixed phrases, authentic readymades, for he knows that it is very healthy to demonstrate that the communicative and emotive capacity of art lies not in the ridiculous pretence of creating its elements. Like the best of gardeners, who does not claim to have invented grass or roses. Things are going badly if these are artificial.

In the same way as the tightrope walker or Augustus, he delights in being faithful to a palaeotechnical, old-fashioned, staged or déclassé visual world, like that of old automatons or the props of illusionists.

He does not fool around with ‘modern’ images in his visual poems. His world is that of the map or scholastic rudiments, of playing cards, of the game of draughts, of the old steel engraving, of the conventional envelope, of umbrellas, etc.

By accepting readymade images, he thus leaps over the pretensions of ‘creativity’ and heads towards the idea without intervening in the forms.

On the other hand, the choice of pairs of found images underlines the fact – to the detriment of the image – that art never says that which it represents. Brossa represents without intervening in the representation, for he knows that what he is saying is something else, specifically something invisible resulting from a deep reading of the relationship between one image and another.

Reaching the idea of the poem in this way represents a cleaner operation than reaching it through traditional art forms, precisely because he has chosen a vulgar iconography that, by the very fact of being so, assumes the category of conventional sign.

This choice saves his visual poems from the danger Kossuth denounces when he says that form tends to sully ideas.

Alexandre Cirici

October 1979