- Dates

- —

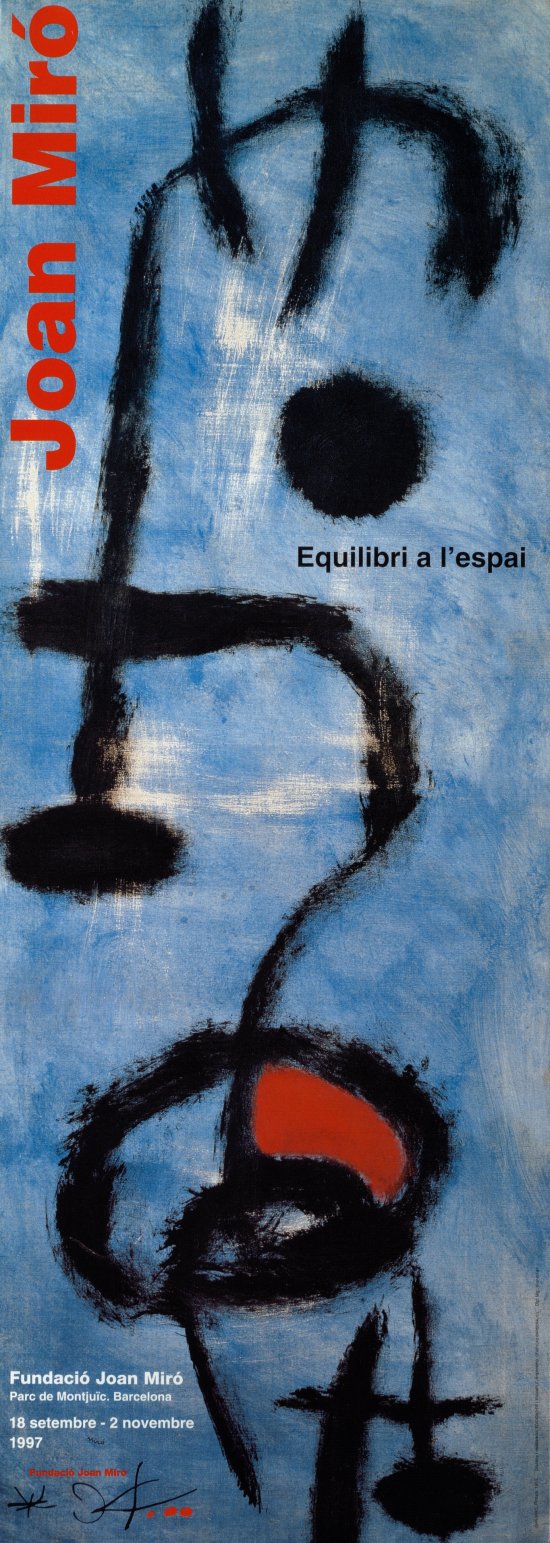

Joan Miró: Equilibrium in Space

‘Balance’. This was Joan Miró’s answer to the question of the secret of his work. As in Oriental art, Joan Miró’s painting is the result of a wise balance between surface and line, full and empty, black and colour, and so on.

It is in emptiness that the pictorial event takes place. Ever since the 1920s, the empty backgrounds in Miró’s paintings, although carefully worked, were already as important as the space occupied by the main element of the composition. As in Oriental art, emptiness is not a non-existent thing in Miró’s compositions, but a dynamic element. It is the place where transformations take place. It is where the full reaches its maximum expressiveness.

Orientals claim that emptiness looks towards fullness. Emptiness, that which is not there, is the protagonist of the composition, because it is the receptacle of what is there.

The minimal expression that Miró inscribes onto emptiness is the black line, which, as Zang Yanyuan said, is true painting because it is a line that comes from the dictate of the spirit and is not made with a ruler.

It is precisely this line, which seems to be an extension of feelings, that in Oriental painting gives form to calligraphy, which adds a new dimension to painting: that of time.

Calligraphy was not foreign to Miró’s work either. As early as the 1920s, graphic elements were included in the composition, both for their meaning and for their visual content. Later, in the early 1940s, when he painted his Constellations, the titles of the works are like short poetic forms, similar to haikus. Years later, through a natural process of purification, the poetic inscriptions would become simple graphic signs in Miró’s paintings.

But these graphic elements are not the only thing that links Oriental painting to the work of Joan Miró. If we look closely, we can note that there is a close correlation between the subjects they deal with. Landscape, a major theme in Oriental painting, is also often present in Miró’s work. It was in Mont-roig, in contact with the landscape, that Miró decided to devote himself to painting. It was also there that he later broke away from immediate reality to create his vocabulary of signs. These signs, which were the interpretation of what he saw through feelings and emotions, are not so far removed from the Oriental principle that claims one must have memorised nature before painting.

Anonymous characters – ‘woman’, ‘Catalan peasant’, etc. – animals, plants, etc., common themes in Oriental painting, are also common in Miró’s painting. In both cases, they do not speak to us of a concrete reality, but of universal concepts.

It is not surprising that Miró’s art has always been well received in Japan. This explains why some of his most important works are currently in Japanese museums and private collections. One that occupies a prominent place among these collections is that of Kazumasa Katsuta, an art lover by family tradition and personal interest. Thanks to his generosity, we are now able to present the exhibition Joan Miró: Equilibrium in Space at the Fundació Joan Miró.